“…our children shouldn’t have to be afraid. I shouldn’t have to be afraid when they walk out the door.” 1

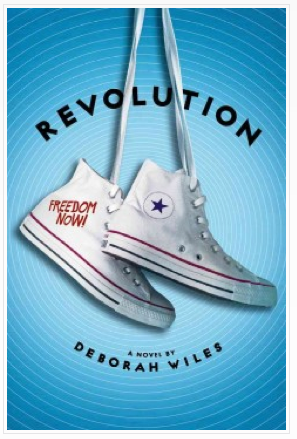

Last week, my 5 a.m. consciousness struggled to place these newscaster’s words. Somehow, Deborah Wiles’ Revolution, fresh in my mind, projected like a newsreel right into the morning’s story. This news was Ferguson, MO, not Wiles’ Greenwood, MS account. Sadly, I had the same feeling several weeks before.

I had been begun Revolution, a documentary novel of Freedom Summer, 1964.

“The air in Fairchild’s, which always smells like bacon and lettuces and yeasty bread and sawdust and air-conditioning in the summer, was laced with the smell of uncertainty then, and there was a hush from some of the white customers—you could feel it. It was a bristly feeling.” (p. 226)

Wiles has a way of making her readers feel it by placing us in the footsteps of young people. We readers see through their eyes, like fragile windows—smudged, cracked, broken, and mended.

“I asked Daddy the question I most wanted to know the answer to: “What’s going to happen?”

“We’re going to watch, Sunny,” he answered me, “and stick together. Everything will be all right.” (p. 206)

That was when a news report from this summer, July 2014, started up like a movie in my mind. A correspondent was sharing stories of two families sheltering during the escalating conflict in the Gaza Strip.2

In Ashkelon, Israel, 30-40 neighborhood family members hunkered in an underground concrete bunker.

“My kids are very anxious,” [one mother says]. They won’t go home to sleep, or shower, or eat…they’re terrified.” “Things are not OK,” [her 10-year-old son says]. “I’m scared.”

The correspondent asks the boy if he ever thinks that kids in Gaza might feel the same. “My mother told me there were sirens there, too,…and those kids also have to run away.”

In Gaza City, families have no bunker to defend against bombing.

“Sometimes I lie,” [says one father]. “I tell my kids, ‘Those aren’t bombs; they’re fireworks.’ When it’s huge, I try to act carefree so they’ll see me and feel reassured.”

“We feel so scared, ” says one 10-year old. The report continues, “she is angry that Israelis can hide in shelters, while her family and people are killed.” When the correspondent asks the girl if she wants Israeli kids to die too, she responds, “They are like me. They have rights. They shouldn’t die. They should be protected, just like we should be protected.”

In an interview with teachingbooks.net, Wiles was asked why she chose to write about Freedom Summer:

I wanted to show the larger arc of our nation’s history, juxtaposed against an individual’s smaller arc. History is made by individuals, one moment at a time. By experiencing Sunny’s walk through it [in Revolution]…, readers see that, choice by choice, they craft a life.3

Wiles has crafted a masterpiece. The angst of youth amidst a rapidly changing, chaotic period colors it. Although poignant photographs document the time — the Beatles, soldiers in South Vietnam, Willie Mays, Freedom Houses — in black and white, this tale’s young heroes, both black and white, see in all shades of gray as they search for understanding and meaning-making. Notably, each chapter’s beginning page is vertically edged with a scale of grays ranging from black to white extremes, reminiscent of a test print pattern. Though subtle, readers see what uncertainty looks like.

Events escalate toward the day black communities line up to claim their voting rights through registration. Standing by their side is an army of college-age volunteers from the North and the West. Bob Moses, the quiet son of a Harlem janitor, had organized this massive group. “They won’t pay attention to us if we die…but bring kids here from the North, from the West…and people will pay attention. And, most important we need their help. We need to work together, black and white together.” (p. 70) Wiles’ young main characters are coming of age, seeking to identify with the fire, the courage and reason just a few years more might yield.

Seeing in black and white is not a youngster’s propensity, so as this novel unfolds, we feel the deep struggle, and marvel at the choice that ultimately places a dying black boy in the care of a broken-hearted white girl. She desperately petitions a deaf-eared physician: “I am covered in his blood and nothing has happened to me!” Suddenly, all gray is punctuated with red. Understanding has dawned. The depth of her empathy, of our reader-empathy, is palpable.

“Whose side are we on?” That was the other question I needed to ask.

“It’s more complicated than that,” Daddy said. “We’ll keep talking. Right now, I need to get you to Meemaw’s…It will be like old times,” Daddy said.

“I didn’t like the old times,” I answered. (p. 206)

That was early in Wiles’ Revolution.

“I’m ready for this situation to be over but I don’t want to go back to the old normal; I want to go back to a new normal,” says Ken Cieslak. He says “the new normal” means caring about what is happening to everyone in St. Louis County, not just the neighbors on your block or who went to your high school. He says the old normal was isolation. The new normal they’re hoping for is…to laugh, learn, listen and come to know each other.4

That was last week in Ferguson. A hope for things yet unseen; an arc of history, mending broken windows.

References

1 http://www.npr.org/2014/11/27/366956579/damaged-businesses-vow-ferguson-will-rebound-from-violence

2 http://www.npr.org/blogs/parallels/2014/07/09/330183767/on-opposite-sides-of-israeli-gaza-border-feeling-the-same-fears

3 http://www.slj.com/2014/06/standards/curriculum-connections/revolution-a-conversation-with-deborah-wiles/#_

4 http://www.npr.org/blogs/codeswitch/2014/11/24/366308090/ferguson-forward-churchgoers-seek-a-new-normal